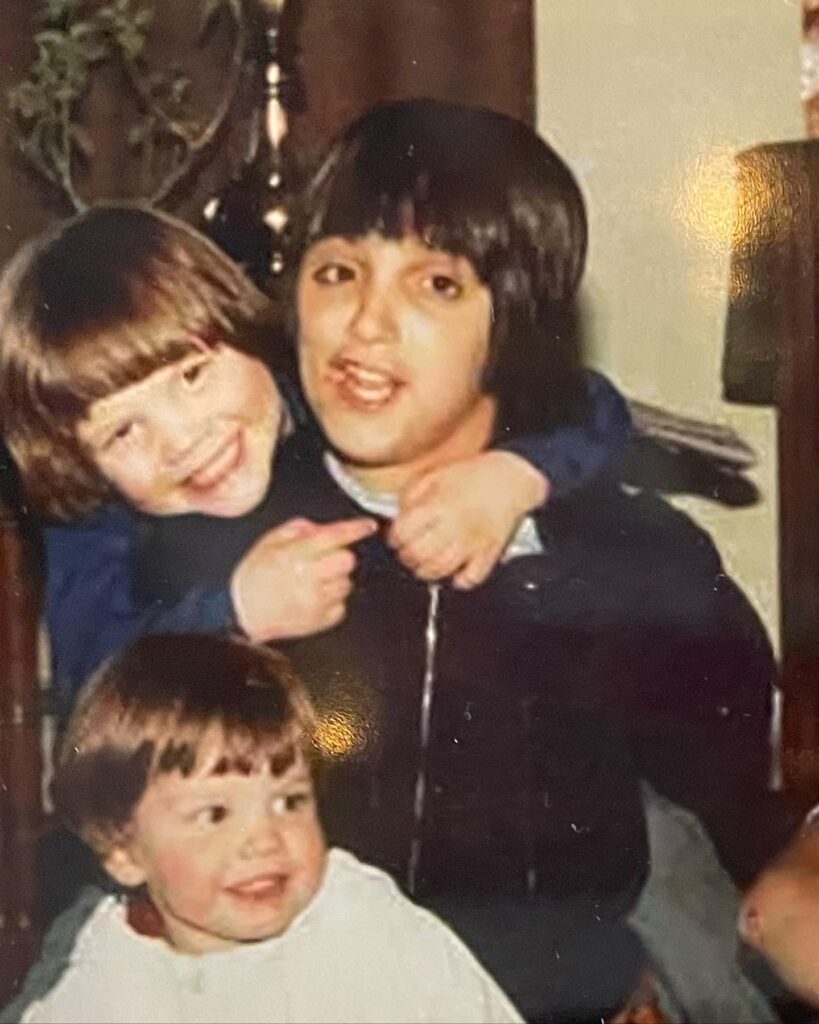

I once wore your clothes. This thought would not leave me alone when I heard what happened to you, I repeated it over and over in my mind, at once a memory and a means of drowning out what I didn’t want to hear. A coping mechanism, a form of denial. No, see, you can’t be gone because I once wore your clothes. So goes the logic of grief.

I thought you were cool, before I knew what cool meant or had developed my own definition of what represented it. At first I felt you were cool because of all of your Older Kid stuff. Seven years my senior, your bedroom dominated by a drum set, posters of Ozzy and the Dead on the walls, a closet full of toys you’d outgrown, more Atari games than I could ever hope to play. You had so many cool things, and since I had so few, I pined to live in your world.

But you wouldn’t have been cool if you hadn’t shared your stuff, and yourself. You weren’t precious about any of your possessions, no don’t touch my stuff grumbling that a younger cousin might expect to hear from an older one. You did not give a shit if I wanted to dig through your closet to find Run Yourself Ragged, a weird marble/boardgame that enthralled little-kid me for some reason. You did not care if I dominated Atari time playing all the games you had that I longed for. You even let me sit on your drum throne and take few whacks at your kit. Having met many drummers since then, I realize how rare and generous this was.

I had the impression you enjoyed my enjoyment of all your stuff. You were a lot like our grandfather, who loved to watch all of us run in and around his house, who never once told us to slow down or don’t do this or that (save for cases of potential danger). Our grampa loved to have fun and watch others have fun. You did too.

I once wore your clothes because I had to. We would visit your house for Thanksgiving or a birthday or a summer barbecue and while I was marveling at all the cool stuff in your room, your mom would give my mom a large bag of clothes you’d outgrown long ago. This was a lifesaver and a wallet-saver for our family. New clothes were largely unattainable for us, or at least unattainable at the rate at which growing kids need new clothes.

There was a time when I would think of this fact in moments of self pity, an exemplar of childhood privation—oh poor me, clothed in hand-me-downs from my older cousin. In the moment, though, I never minded. For one thing, I was the kind of kid whose daily wardrobe choices were determined by whatever was left at the foot of my bed by my mom when I woke up in the morning. For another thing, I thought the clothes were cool, because they were yours, and because they were old. The history dork in me, already burrowing his way to the surface, was impressed by anything as old as you, the only person I knew who was so much older than me yet not an adult.

If anything, it was a plus to me that the clothes were outdated, like a t-shirt with a cartoon Mean Joe Greene declaring his intention to win “one for the thumb in ‘81”, which I wore despite having no knowledge of the Pittsburgh Steelers or their legendary defensive tackle. I didn’t mind the red sweatshirt with the old Patriots logo on it because, again, history dork, so a colonial looking guy was right up my alley even if football wasn’t. Already obsessed with Peanuts, I certainly didn’t mind the sweatshirt showing a sweaty Snoopy in mid-stride accompanied by the simple legend JOGGING.

I once wore your clothes. In most family photos I am wearing your clothes. In most school pictures I am wearing your clothes. When I dig up old photos, even when you are not literally in the picture, I can’t look at myself without seeing you.

This is where one might put a heavy handed metaphor about walking a mile in someone else’s shoes. I can’t fully claim that. My childhood was not great but my not-greatness paled in comparison to yours. Even when I was little I knew you had a hard life from the moment you were born. I had seen pics of you as a toddler with your head bandaged or in a helmet. I was never told anything beyond the fact that you “had problems” when you were younger, and I never asked what those problems were because of course I didn’t, I knew that’s not a question you ask and what difference would the answer make anyway. I did know that other kids called you a monster, I was told they literally used that word, monster, and that made me so sad and angry to hear about. Little kid me wanted to beat those mean kids up even if it happened long before I was born. It sounded like the beginning of a super villain origin story. Get called a monster enough times and you may long to show the world what a monster is really like.

That was not you at all. When I think of you I think of your laugh, so unique and given so freely, like a child’s laugh. Your laugh gave me the same delight and joy I still feel today when I hear little kids laughing. Laughing at Looney Tunes, Woody Woodpecker, Mystery Science Theater 3000, which you first told me about because you thought I would love it and of course you were right.

I once wore your clothes, though I had to wait a while to wear them. You were seven years older than me, a titanic age gap for a little kid. You were almost like an authority figure, though different from the grownups in the family. Adults have the ability to tell you what you can and can’t do, but an older kid can show you what you want to be. Your love of fun, your love of kid stuff, your continued presence at the Kids’ Table every holiday, with no seeming desire to level up and be with the adults, this showed me it was okay to be a kid, and to stay a kid at heart forever.

Whenever we were at our grandparents’ house, there would come a moment I both dreaded and longed for, when you and your brother would declare that it was time to go to The Fightin’ Room. Me and the other younger cousins would protest no, anything but that! like the hapless victims in a horror movie, even though we all loved it. The Fightin’ Room was a guest bedroom at the back of the house, with two twin beds spaced a kid’s leap apart, which you and your brother would bounce us off of while doing mock wrestling moves. We, the younger cousins, took it much too seriously, climbing on your backs, elbowing you in the ribs, landing little kid blows to the backs of your heads, pulling on shirts that I would one day inherit. I’m sure this hurt you more than a little bit. I don’t remember either of you ever getting mad or retaliating.

I still think of my grandparents’ house as a refuge. They lived right next door and I would go there all the time when I was little, to avoid my own house and its fraught atmosphere. I never had to call ahead, I barely had to knock, the door was always open and I knew that I would be safe there. The Fightin’ Room was a part of that. It was the ultimate expression of love, really, a place where you could get tossed around like a ragdoll yet know that nothing bad would happen to you.

I once wore your clothes, and felt like I put them back on whenever I saw you. Perhaps this is not how things are for everyone, but I know that when I see someone I grew up with, in many ways I feel like a kid again, I can speak a special kid language of references and memories, I can revel in the things that delighted me as a kid no matter how stupid they are. And when I am allowed to act like a kid again, I am reminded of what is good about being a kid.

Not everything about being a kid is good, and certainly not everything about my own childhood was good—I’d say the batting average on that was pretty low, actually. I’d go as far to say that thinking everything was much better in one’s childhood is a dangerous delusion bordering on the fascistic. All this said, there are good things about being a kid, namely the fresh eyes that all kids have when they are experiencing things for the first time, figuring them out, both alone and with other kids. Having a child’s eyes, or the ability to remember what it’s like to view the world with a child’s eyes, is an essential part of being human. Adults who won’t attempt to do this are withered husks and, at best, not much fun to be around.

I am fortunate that I still have many people I grew up with in my life. But to lose one of those people, and to lose the first one I knew, it feels like some of that permission to be a kid has been taken from me along with you. There were things we shared, and in your absence I feel I have no one to share them with. They now rest somewhere within me, sitting on one end of a seesaw looking for a partner that will never show again.

When I got the news you were gone I had this great compulsion to rewatch Wings of Desire, the Wim Wenders film about angel-like creatures in Berlin that watch mortals from a distance, unseen by those they observe. Perhaps I hoped that in your final moments you had something like what is shown in the movie, these invisible entities finding people at their lowest ebb and giving them a modicum of comfort by being in their presence. Perhaps I just wanted to rewatch the scene with Peter Falk talking to one of the unseen angels about all the joys of being alive, a scene that always brings me to tears.

Mostly though, I think I wanted to hear “Song of Childhood,” a poem written by one of the screenwriters, pieces of which are recited as the movie progresses. Its opening line, Als das Kind Kind war (“When the child was a child…”), is repeated throughout the poem and the movie. It is a poem about a child observing the world they find themselves in and trying to understand what they see. It is a poem about how this observation changes as one ages, and what doesn’t or shouldn’t change.

I thought of that poem again at your funeral. Traffic was very bad on the way there and I got to the church just as mass started. As I arrived I slid into a pew and saw my little nephew, being held by his mother in the next pew up, smile and wave at me. The sight brought to mind the funerals I went to as a kid, funerals I went to with you, almost always for people we didn’t know or barely knew, and we knew the adults would be sad and that we couldn’t go too nuts but it was still a family gathering, which meant we got to see each other and fool around within reason, at the back of the church or another room at the funeral home. We could laugh, play a game we made up on the spot using whatever was around us, a thing done by kids and too few adults. We got to have fun, even then.

Later I saw my nephew playing on the floor of the church, poking a stick he’d found outside under the pew, stabbing the air with it like it was a sword. It was another reminder of what only a child sees, treasure in the detritus of nature. A child can look at the ground and see a stick or a few leaves and believe it is the greatest, most beautiful thing they’ve ever seen, it must be theirs, it must remain with them forever. Most adults don’t see this, and even if they did they’d know the leaves will rot, the stick will just take up space, it’s all temporary so what’s the point in trying to keep it.

But everything is temporary, you, me, everyone else, the earth itself. A person can either despair in that or, like a child, delight in it. I know I had eyes to see that once. I know you did too.

The scene made me think of the final lines of “Song of Childhood”:

When the child was a child

It hurled a stick at a tree like a lance

And it still quivers there today

I once wore your clothes. I will always wear your clothes.