Major League Baseball has seldom led. Leadership on any point has never been part of the DNA of an organization that relies on the exceptional but fleeting talent of young men to line its pockets. This was certainly true in days of yore, when league ownership was dominated by weepy alcoholic used car dealers who resisted every player’s attempts to be paid fairly with the unhinged fervor known only to small business tyrants. It is doubly true now that those tyrants of old have been replaced by third-generation failsons who look upon their MLB properties as public money delivery vehicles first, all competitive concerns far down their lists of priorities.

The league did not lead in any fashion when it came to the recent explosion of legalized sports gambling across the nation, but has been happy to reap the rewards that have come its way once this began happening. It is now impossible to watch any baseball broadcast without being assaulted by advertisements for Draft Kings, Fanduel and their cohorts, regional sports networks inserting over/under calculations into their rotating score crawls while sideline reporters remind you it’s not too late to get a quick parlay in before the end of the fifth inning. And if you go to watch your favorite team play in person, that team might allow you to do so in a racino-style sports book, in case you find the on field action too boring and need a little more skin in the game.

These partnerships brought with them a contradiction that was immediately obvious to anyone familiar with MLB’s history. Unfortunately, baseball’s history is a subject that most of the league’s current owners and its commissioner, Rob Manfred, have a glancing familiarity with at best. The 1919 “Black Sox” scandal, in which eight players were accused of throwing that year’s World Series at the behest of organized crime figures, made it crystal clear how dangerous it would be to allow players any rope whatsoever when it came to gambling. A sport that permitted its players to be disincentivized via betting would cease to be a sport. This is why the league enacted Rule 21, which stated unequivocally that any player proven to have bet on baseball would be banned from the game for life, no exceptions. (Well, some exceptions.)

Flash forward to the Caesars Sportsbook era and this no tolerance policy suddenly stood alongside a new status quo that not only tolerated gambling on its games but encouraged it. Before long, the bitter fruits of this bipolar policy ripened. For as lucrative as these partnerships have been for the league and its owners, they have accrued few benefits to its fans or its players (unless crippling debt and death threats can be considered benefits). If it’s too much to ask MLB to look out for the best interests of the fans and players who make their wealth possible, the league should have been spooked by the sudden epidemic of gambling-related suspensions that have followed its full embrace of sports betting apps. And if that trend didn’t induce some serious pants-filling fear in the owners, the gambling scandal that erupted last year and almost took down the sport’s biggest star in decades most certainly should have.

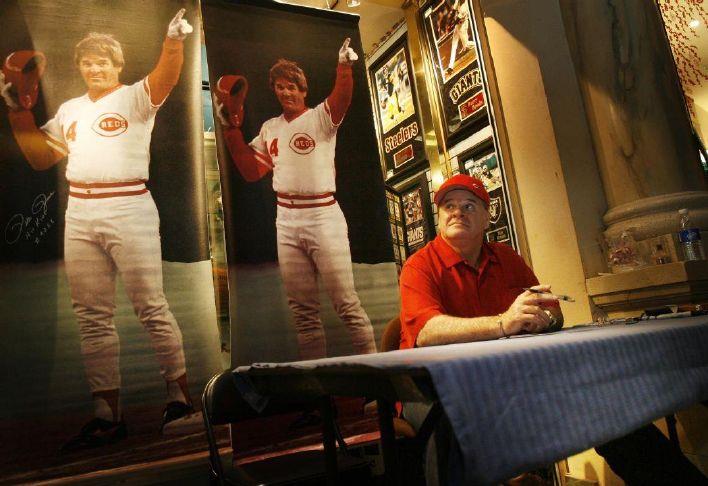

Gambling in baseball also revived the memory of Pete Rose. This was not the worst knock-on effect of the league getting in bed with sports books, but it might be one of the most unpleasant. Rose received a permanent ban from the game in 1989 for a history of gambling on baseball that stretched back to his earliest days as a ballplayer, and which included the eminently bannable offense of betting on games involving the Cincinnati Reds at the same time as he managed them. The revelation that the sport’s all-time hit leader had bet on games he managed was nearly as huge a scandal as the White Sox’ betrayal 70 years earlier, and nearly as traumatic to its reputation.

Rose was a case study in someone who did everything in his power to be undeserving of sympathy. He lied about his gambling at every opportunity, first denying he did it at all, then insisting he never bet on baseball, then averring he never bet on his own team before vowing he only bet on them to win. Only death prevented him from changing his story further. His ban from baseball was essentially a plea bargain—he agreed to the ban in exchange for MLB not pursuing their gambling investigation, as it would have revealed extensive mob connections that could easily have led to criminal charges—and yet he spent the rest of his life describing the ban as an unfair punishment imposed on him by a cruel commissioner (Bart Giamatti, who was so traumatized by the affair he dropped dead of a heart attack eight days after its resolution). Rose never apologized for any of the above, and lived out his post-baseball life with the narcissistic defiance of someone convinced he was the only righteous person in the world. And none of this touches on his immense and horrifying outside-the-lines crimes, which should have earned him a place under the jail.

The reinstatement of Rose was long a crank cause celebre. His crimes were often dismissed with the standard Nixon defense of “everybody did it, he just got caught”. When steroid scandals exploded in the early 2000s, his champions screamed about how the use of PEDs was much worse for the game’s integrity. All of this was sophistry of the highest order, but it was largely confined to barrooms and talk radio. Any hope Rose might actually be reinstated was not to be taken seriously, because Giamatti’s immediate successors never broached the subject if it could be helped, and because Rose’s reprehensible post-ban behavior spoke volumes. He was a man who never sought redemption. I would say this was because deep down he knew he never deserved it, but there is no evidence he had anything close to that sort of introspection or self awareness.

Then MLB embraced gambling, and more and more people—many with no living memory of Rose as a player, or of the scandal that took him down, or the many things he’d done to shun forgiveness for that scandal—wondered aloud about the hypocrisy of a league that partnered with betting apps banning someone for gambling. There were many potential responses to these charges, and an organization with the ability to lead could clarify its position. It would be very easy, for instance, to provide a distinction between sanctioning fans who choose to gamble and punishing players who violate league rules that threaten the sport’s integrity.

But Major League Baseball has seldom led. That is why MLB has announced to the world it will tolerate as many gamblers in its midst as possible, even dead ones. That is why we are told we must welcome back the mouldering corpse of Pete Rose.

Many have said that Rose’s reinstatement is directly related to Donald Trump championing his cause, and this is likely true. As is the case with other craven corporate entities who bowed to his whims, voiced or assumed, MLB may very well fear angering the demented toddler in chief, especially when the league’s wafer-thin anti-trust exemption can be revoked by any Congress willing to take up the cause. But in my view, Rose’s reinstatement is less the following of a direct Trump order than it is the mimicking of a general Trump vibe. Namely, the Trump era trend of assaulting the public with an endless array of cancerous little dickheads, for no other reason than their elevation will infuriate anyone with a sense of fairness or morality.

It could be a reality show washout who is charged with crashing planes, or a FOX News fascist surrounded by a permanent cloud of Popov told to un-wokeify the military, or it might be the legion of sniveling groyper Wormtongues whispering Great Replacement talking points in the president’s ear. Every day, it seems, we are reintroduced to some monster who’d become (in)famous in a non-governmental capacity, whose many crimes are ignored if not celebrated, and who, we are told, will be given immense power over our lives. What these people actually do with that power is of course the worst aspect of all this, but almost as bad is the fact that we cannot escape seeing them, or thinking about them, these otherwise unemployable, intolerable monsters whose sole function is to squat in valuable real estate in our collective psyche, their hands an inch from our faces, sneering Does this bug you? Does this bug you? I’m not touching you...

Now add to this list Pete Rose, a man who sacrificed a Hall of Fame career to a crippling gambling addiction, who never sought treatment for that addiction, who never apologized for a single crime he ever committed, who went out of his way to be undeserving of forgiveness until his dying breath. He is reinstated to a game he did everything in his power to destroy, to the seal-like clapping of people who celebrate him for the mere fact that this celebration will enrage people they hate (and also because they applaud his off-the-field atrocities).

How fitting that MLB’s elevation of Pete Rose comes immediately on the heels of the diminishing of Jackie Robinson. The major league debut of Robinson in 1947 as the league’s first black player was a rare case when MLB actually did lead, coming at a time when most of the country was still segregated, functionally where not by law, and public opinion was nowhere near a consensus that this was wrong. His career and life were heroic by any definition of the word, but we do not live in an era of heroes. Now MLB speaks of Robinson as if he were merely a very good player, whose accomplishments and bravery must not be mentioned lest it offend the dying brain in the Oval Office, while rolling out the red carpet for an unrepentant degenerate gambler and pedophile rapist.

If only Pete Rose could have lived to see his sociopathic dream come true: an entire nation talking about him, sports writers falling all over themselves to forgive a man who never wasted a single breath to ask for forgiveness. Finally, the moment has come when our world has become just as shitty as he was.