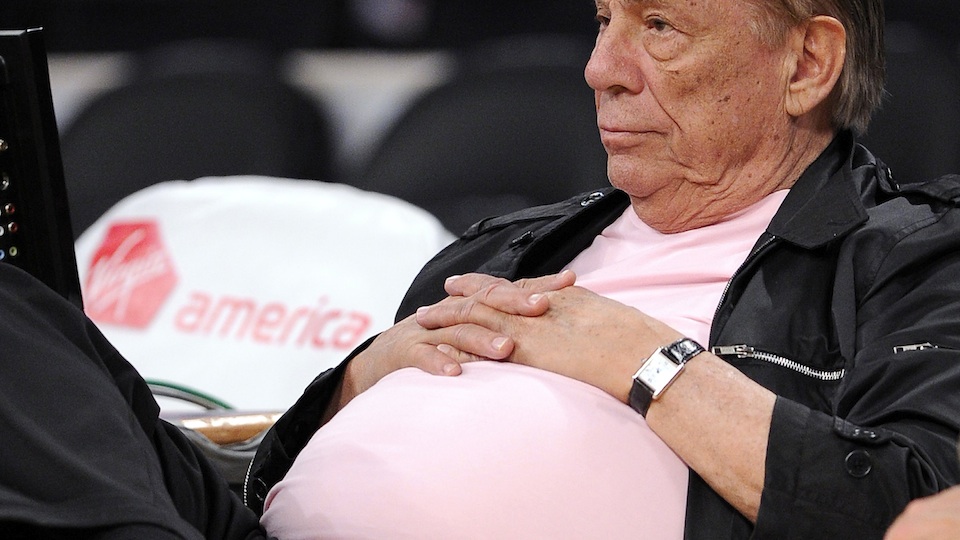

As the current controversy swirls around Donald Sterling, many people are surprised he could be bounced from the NBA for making racist statements when he is a horrible human being who has done many horrible things over the course of his horrible lifetime. In his basketball dealings, the Clippers owner has consistently treated his players like chattel. In his other businesses, he’s even worse, as he did his best to impose racial quotas on his Los Angeles real estate properties and celebrated beating lawsuits brought against him by elderly widows.

For many, Sterling’s potential demise stemming from something he said in a secretly taped phone conversation feels unsatisfying, like Al Capone going to prison for tax evasion (or maybe racist tax evasion). He said some hideous words—the reasoning goes—but they were just words, which pale in comparison to his past actions.

Such reasoning fails to understand the character of what our world has become. In the 21st century, we have little else but words.

If you’re fortunate enough to live in the First World (the arena where the Sterling mess is being discussed in earnest), chances are you spend your day dealing in total abstractions. Rather than make tangible objects, you arrange words and send them to other people, who read them and arrange their own words in response. Or you interpret data into recommendations for possible future actions for someone else higher on the chain of command, someone you may never see.

If your job does involve making something, it is probably an app or a web site or something else that is, at its core, a carefully arranged series of ones and zeroes. The highest paid, sexiest jobs in our universe hinge on the writing and interpretation of huge blocks of letters and numbers and symbols we call code.

More and more human interaction is performed through some kind of electronic intermediary (the Internet, or some form thereof), free from physical contact and other sensory input, sometimes even free of any sort of context. As our world has grown increasingly abstract, the abstract has increased in value.

Words—abstract expressions, as opposed to action—mean more now than they have at any other point in human history. There was once a wide gap between saying I’m going to punch you in the mouth and actually doing it. The distinction between the two narrows more and more every day.

In such a world, an action is not as important as an event. An event is something that allows people to react publicly (on the internet) in the abstract form of words.

Donald Sterling made two fundamental mistakes that are indicative of him being a product of the 20th century (or, based on his racial politics, maybe the Dark Ages). His first mistake was assuming there’s any such thing as a private communication. His second was making his racism an event. He did so by condensing his horrendous views into a bite-sized chunk that could be easily disseminated and reacted to in the abbreviated channels in which most of us now interact.

In a world in which most of us get our news from condensed media like Twitter, Facebook, or frantic texts from friends and relatives, an event is not important unless it can be quickly understood and engender an immediate reaction across a wide swath of people. Such events have to possess as little ambiguity as possible, and allow people to construct outsized emotional reactions.

The events that have traction in this world are ones that allow uninvolved observers to climb atop soapboxes and adopt stances that bestow upon them a feeling of abstract righteousness. Something will stay in the news as long as it permits people to feel their reaction to it means they’re making a stand, even if that stand consists exclusively of tweeting about it once a day.

These abstractions push aside events that are, materially, far more important. A civil war in the Ukraine is kind of a bigger deal than anything Donald Sterling said, but a civil war has way too many complicating factors to afford any casual observer the luxury of feeling they’re on a side that is totally “right.”

An “important” event also has to emerge, progress, and reach its endgame in a timely manner. The missing Malaysian Airlines flight was enormous news for a few weeks, due to the weirdness of the mystery and human sympathy for those on the flight and their families. Then, it became clear that the story’s resolution was nowhere in sight. Now, as far as the internet is concerned, that story is as over as a TV series that never figured out its own denouement.

Had Sterling’s remarks left any room for interpretation, he could have continued owning an NBA franchise no matter how many employees and tenants he harassed. Instead, he said something so cartoonishly racist it ripped through the internet at lightning speed. It both allowed people to stand firmly against a specific person and a specific thing, and it seemed to point to a specific, imminent conclusion; i.e., kicking Sterling out of the NBA.

Should the NBA’s official reaction to Sterling’s words drag on for any length of time (which it almost certainly will), the internet will be happy to move on to another target of outrage, confident it did its part in getting rid of him. Even if Sterling remains a franchise owner, we will at some point stop talking about him after having talked about him at length for what seemed like a really long time, and that will be sufficient punishment in some people’s minds. If no words are spent on your behalf in this abstract world, do you even exist?