Click here for an intro/manifesto on The 1999 Project.

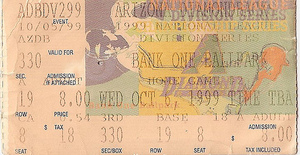

The Mets prepared to play the first playoff game at Shea in 11 years, and their first playoff game in the bright lights of prime time (after playing the first two games in the wee hours, New York time). For one night, the coverage switched over the NBC and the much more prestigious (and competent) play-by-play stylings of Bob Costas. Which reminds me: I wish the MLB Network (or somebody, anybody) would use Costas for play-by-play duties again. I’m not a huge fan of his in other contexts, but as a game caller, he’s one of the best, and there is a dearth of national baseball broadcasters who don’t totally blow these days.

The Mets prepared to play the first playoff game at Shea in 11 years, and their first playoff game in the bright lights of prime time (after playing the first two games in the wee hours, New York time). For one night, the coverage switched over the NBC and the much more prestigious (and competent) play-by-play stylings of Bob Costas. Which reminds me: I wish the MLB Network (or somebody, anybody) would use Costas for play-by-play duties again. I’m not a huge fan of his in other contexts, but as a game caller, he’s one of the best, and there is a dearth of national baseball broadcasters who don’t totally blow these days.

On what should have been a joyous occasion for the team and its fans, the Mets were beset by dual obstacles: one an annoying distraction, the other a serious impediment to their playoff hopes.

The distraction came in the form of leaked material from an upcoming Sports Illustrated interview with Bobby Valentine, which included quotes from the manager taken during the Mets’ disastrous trip to Philadelphia in September. Which quotes were the most inflammatory? Take your pick.

Perhaps it was his description of his team: “You’re not dealing with real professionals in the clubhouse; you’re not dealing with real intelligent guys.” Or his dismissal of a players-only meeting held at Veterans Stadium that weekend: “There’s about five guys in there right now who basically are losers, who are seeing if they can recruit.” Or his dis of rival skippers: “A lot of managers fear that some day they’ll have to be on a panel with me and be exposed.” (He also said he feared the influence Bobby Bonilla had on the team, but that was hardly controversial. If anything, it was an opinion shared by everyone connected with the team not named Bobby Bonilla.)

Players’ reactions ranged from muted disappointment to dismissal to eye-rolling. One unnamed Met told the Daily News, “Guys care about what’s in here and doing what we have to do for ourselves. We don’t care about what the manager says.” Valentine’s pregame response: “If the shoe fits, wear it. If it doesn’t, don’t worry about it.”

No matter what any player said to the press, the whole sordid affair was far too reminiscent of the dysfunctional atmosphere that surrounded the club at the beginning of the season. Not to mention, they had one much bigger thing to worry about.

Back in April, the Mets’ home opener was soured by the absence of Mike Piazza, who was on the DL with a sprained knee. Their first home playoff game opened on a similar down note. Piazza took a shot to his left thumb in game 2, aggravating an injury he sustained on a foul tip from Ron Gant in a game against the Phillies in September. The catcher got x-rays, which showed no break, so he took a cortisone shot in the hopes of a speedy recovery.

Unfortunately, the cortisone shot resulted in a rare allergic reaction that caused his thumb to swell up even more, to the point where he couldn’t bend it at all. So three hours before game time, Piazza was a surprise scratch from the lineup. The good news, if there could be any when losing your most powerful offensive threat, was that the extra time off would help him rest the myriad of injuries sustained during a year behind the plate. His shoulders and knees were also in some serious pain. Before the thumb flared up, he said he planned to spend the day bathed in ice.

Piazza had been playing with a banged-up thumb for weeks, without complaint, because every game was so important for the Mets. And yet, because he rarely vocalized his aches and pains, and because of his mellow nature, many sportswriters found him inscrutable and not “leadership material”.

After he professed himself happy to escape Phoenix with a split of the first two games (an attitude evidently shared with many of his teammates), an incredulous Mark Kriegel wrote in the Daily News, “He grew up outside Philadelphia…[b]ut Piazza’s persona remains that of the laid-back Californian. Sometimes you wonder if he’d rather play drums than baseball.”

Now Piazza would not be playing baseball, as Kriegel suspected he preferred, and the Mets would have to find a way to win this game (and possibly more) without him. In a local pregame show for NBC-4, GM Steve Phillips told Len Berman he was “pretty confident” Piazza would play in game 4, but that was more a hope than a diagnosis. Valentine said Piazza could possibly pinch hit, though it would have to be an emergency situation. What would constitute an emergency?

“Orel [Hershiser] at the bat rack in the 14th inning,” he said.

With or without him, the Mets were not sitting pretty just because they were back at Shea. The Diamondbacks were no pushover on the road, compiling a 29-10 away record after the All Star break, the best in baseball.

If it was any consolation, backup catcher Todd Pratt had played well in Piazza’s absence earlier in the year, batting .319 and hit three homers while he was on the shelf in April. With lefty starter Omar Daal on the mound for Arizona, Benny Agbayani would bat cleanup in his place.

Diamondbacks manager refused to look past Pratt, even if everyone else did. Presciently, he said, “I have known Todd Pratt for a long time with the Red Sox [Pratt was in the Boston organization in late 80s/early 90s]. He has always been a guy that has been able to rise to the occasion. I am sure they would like to have Mike in there, but it doesn’t

preclude them from winning a game and from Todd Pratt having a big game for them.”

Continue reading 1999 Project: NLDS Game 3

But the biggest acquisition of all–in more ways than one–was Randy Johnson, the 6’10” southpaw ace. Ten years later, it can be hard to remember just how dominant he was. His mediocre stint with the Yankees, combined with his twilight years back in Arizona and San Francisco, is fresher in most people’s minds than the prime of his career. But in 1999, Randy Johnson was

But the biggest acquisition of all–in more ways than one–was Randy Johnson, the 6’10” southpaw ace. Ten years later, it can be hard to remember just how dominant he was. His mediocre stint with the Yankees, combined with his twilight years back in Arizona and San Francisco, is fresher in most people’s minds than the prime of his career. But in 1999, Randy Johnson was