It is near-rush hour on the F train which is to say it is crowded but not packed. A pair of drag queens crack each other in a nook by a shut door. One baby wails in each half of the car. The one attacking my left ear is a little more persistent than the one attacking my right. A panhandler says “Excuse me” in a clear smooth voice so he can move past other riders before adopting a pitted groan to give his SPARE CHANGE pitch.

I’m attempting to read Richard Rhodes’ The Making of the Atomic Bomb which is a long and heavy book and not conducive to standing-up-on-the-subway reading but I’m reading it anyway. I’ve read this book before but I recently felt compelled to reread it. I’m not sure why.

We are stalled at the Queensbridge stop when a yell asserts itself above the din. I look down at the far end of the car and see a man in gray packed against a closed door. His brow is knotted as he unsheathes his shaved dome from his headphones.

IT’S CROWDED BUT IT AIN’T THAT CROWDED! he shouts. WHY YOU GOTTA BE ON TOP OF ME?! From where I stand no one appears to be on top of him. I can’t see the target of his yells. I can only see the other riders craning their necks to get a look at the noise.

MOTHERFUCKER YOU THINK THIS IS A GAME? he yells. These words are a signal that tell every pair of eyes to avert its gaze and every head to pivot away. Nothing good has ever happened after these words are spoken. No one ever says YOU THINK THIS IS A GAME?! before handing out freshly baked cookies.

YOU GIVE ME AN ATTITUDE?! YOU TRY THIS CONDESCENDING BULLSHIT WITH ME?! The man was obviously convinced that he of all people should not have to stand for whatever transgression was just visited upon him. The world should have known that he was a man not to be trifled with or a man with a reputation or a man at the end of a long bad day or a man at the end of his rope.

The doors won’t close to move on to the next station. This gives the drag queens enough time to give each other a knowing look and run out onto the platform to find another car to ride in. I contemplate doing the same until a conductor squawks over the PA. For a moment me and all the other riders in the car believe someone will do something about the man’s escalating anger.

The conductor has other fish to fry. I told you you can’t hold the train doors to panhandle, he bleats in exasperated pixilation to some other miscreant. Let go of the doors so the train can move. You do that again and I’m callin the cops. The doors stutter back and forth for a few seconds to chase away this unseen annoyance.

Then the doors shut and we continue on out way but the yelling man is still yelling. YOU DO THIS TO ME?! he spits. Everyone else’s head is cast down. The F is an express once it leaves Manhattan. A long ride lies between Queensbridge and Roosevelt Avenue. It will be an even longer ride with this man screaming and everyone silently begging the train to move faster toward its next stop.

The car takes on the feel of a hospital waiting room. No one can stand to look at anyone else. Everyone expects bad news and they prefer it come sooner than later. The bad news will be nothing compared to the torture of waiting for the bad news.

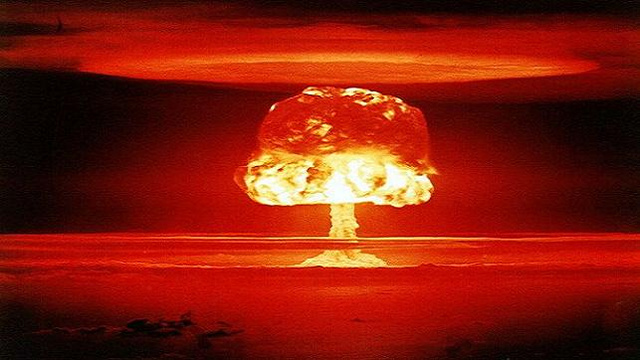

I try to distract myself with my book. The Making of the Atomic Bomb starts with the amazing discoveries of physics in the early 1900s and how these advances laid the groundwork for the weapon to come. I’ve reached the point in the book where scientists first ponder the possibility of fission: Is it possible? Can a reaction be contained? Would this unleash more power than the world can handle? It’s also the point at which the rise of Hitler in Germany sends many of the world’s best physicists to America. At least the ones perceptive enough to recognize the approaching danger. Even some of the smartest people who ever lived had trouble believing the Nazis were going to do exactly what they said they’d do. It was all too monstrous to be real until it was monstrously real.

The Making of the Atomic Bomb is about as accessible as a book mostly about physics can be. Rhodes’ prose alternates between breezy comparisons and touching profundity. But the finer details can be rough to negotiate even without a crazy person threatening to explode in your subway car. Someone who is wailing at a foe who I can’t see and who may have a weapon and may just be hunting in his overcharged brain for an excuse to produce it.

I kept my eyes on the exploits of Niels Bohr and Enrico Fermi and Leo Szilard because they were all past. We all know how that story ended. The one in my car had a more doubtful outcome.

Bohr did not think his compound model of the nucleus boded well for harnessing nuclear energy….THIS AIN’T NO GAME…Einstein had compared it to shooting in the dark at scarce birds…I AIN’T PLAYIN…the efficiency of slow neutrons “might never have been discovered if Italy were not rich in marble”…YOU GONNA DO THAT TO ME?!…The truth was, uranium was a confusion, and no one yet knew…THIS WHOLE CAR MAN THIS WHOLE CAR…Szilard saw beyond “energy for industrial purposes” to the possibility of weapons of war…

The book slowly overtakes the voice. The yelling stops completely as light pierces the car and we approach Roosevelt. Whoever this man felt the need to yell at refused all that time to yell back—assuming he existed at all. Without someone to react with his anger burned up all its fuel and died off.

I dare to look in the yeller’s general direction as I depart for the local. I do not see him. He produced only fright before dispersing into the ether. If only every outburst failed to spark a chain reaction.