Click here for an intro/manifesto on The 1999 Project.

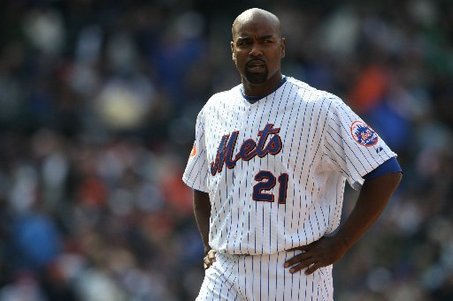

Now that the Mets actually made the postseason, Bobby Valentine could finalize his postseason roster. There were two surprising inclusions: Bobby Bonilla, who’d been as ineffective as he’d been unpopular all year, and Melvin Mora, a September callup with only 31 major league at bats (even though one of those at bats was pretty significant). Not chosen: backup shortstop Luis Lopez and Bobby Jones, who’d been a fixture in the Mets’ starting rotation for years but was injured much of the season.

Now that the Mets actually made the postseason, Bobby Valentine could finalize his postseason roster. There were two surprising inclusions: Bobby Bonilla, who’d been as ineffective as he’d been unpopular all year, and Melvin Mora, a September callup with only 31 major league at bats (even though one of those at bats was pretty significant). Not chosen: backup shortstop Luis Lopez and Bobby Jones, who’d been a fixture in the Mets’ starting rotation for years but was injured much of the season.

The Mets were late to qualify for the playoffs, and now they would be late to start them. Game one of their division series against the Diamondbacks was scheduled for 11 pm New York time, preventing the younger fans from watching and irking the older ones. With all the drama and locations they’d been through in the last few days, Chris Berman (given play-by-play duties for the ESPN broadcast, and only slightly more tolerable 10 years ago than he is now) wondered, “Do the Mets know what time zone they’re in, and more importantly, do they care?” (Answer, according to sideline reporter Buck Martinez: No, and no.)

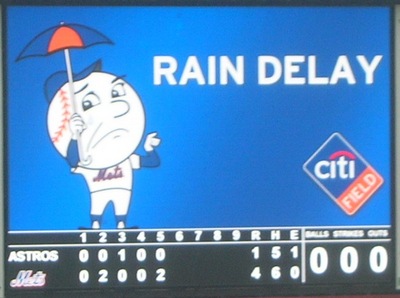

The late start accommodated the local time, the whims of the networks, and the full schedule of playoff games. Earlier in the day, the Astros stunned the Braves by beating Greg Maddux in Atlanta to take game one of their series. Then, the Yankees started their postseason the same way they did in 1998: by pasting the Rangers in the Bronx yet again.

This marked the first playoff game for the Mets since the seventh game of the disappointing NLCS in 1988. They were shut out 6-0 by current Met Orel Hershiser in the series clincher, then spent 11 years in the wilderness.

This also marked the first playoff game ever for the Diamondbacks, a team who spent big in their sophomore season and got immediate returns. The team was not just led by manager Buck Showalter, but crafted by it as well. Showalter had been with the team since its prenatal stages, and there was not a single move the team made without his knowledge (and at least tacit approval). He availed himself of this privilege quite often; in the team’s second year, only nine members from the freshman squad remained on the roster.

Showalter was pitted as the anti-Bobby Valentine. Most newspapers covering the series used words like businesslike to describe him. Other frequently used adjectives included gritty, methodical, workaholic, blue collar. They noted how Showalter had been ejected only once all year, much fewer times than his hotheaded couterpart on the Mets. However, Buck was quick to point out that he admired Valentine, calling him “a great baseball mind”. An opposing manager complimenting Valentine, even begrudgingly, was rare.

Arizona’s free spending ways required a rather large infusion of capital from their investors, prompting immediate comparisons to the 1997 Marlins, who won a championship on the backs of free agents, then immediately sold them all off. Owner Jerry Colangelo assured the public that would not be the case, insisting the additional funds “will put our house in order for the next two years. With the contracts we’ve signed, we are set to compete for four years, and nothing has changed our attitude about that.”

Not everyone was convinced. Despite the acquisition of some big time players, the Diamondbacks saw season ticket sales fall from their inaugural season. The New York Times noted that Arizona had “the distinction of being the only team in any sport to draw fewer spectators finishing first than it did the previous year finishing last.” Even third baseman Matt Williams was forced to admit, “They’re not rabid fans.” The Diamondbacks’ rise to the top was so meteoric that local newspapers had to instruct fans what to do at a playoff game, prompting much ridicule from grizzled New York scribes.

Whether or not the locals noticed, Arizona had quite a year. They did not coast to the end, either, winning 21 of their last 27 games and finishing with 100 victories. Williams had an MVP-caliber season, driving in 142 runs. Luis Gonzalez emerged from nowhere to become a monstrous slugger. Jay Bell rebounded from a lackluster 1998 to lead the team with 38 homers. Tony Womack led the league with 72 steals. Closer Matt Mantei was acquired from the Marlins midseason and shored up the team’s one weakness, its bullpen.

But the biggest acquisition of all–in more ways than one–was Randy Johnson, the 6’10” southpaw ace. Ten years later, it can be hard to remember just how dominant he was. His mediocre stint with the Yankees, combined with his twilight years back in Arizona and San Francisco, is fresher in most people’s minds than the prime of his career. But in 1999, Randy Johnson was at the height of his powers.

But the biggest acquisition of all–in more ways than one–was Randy Johnson, the 6’10” southpaw ace. Ten years later, it can be hard to remember just how dominant he was. His mediocre stint with the Yankees, combined with his twilight years back in Arizona and San Francisco, is fresher in most people’s minds than the prime of his career. But in 1999, Randy Johnson was at the height of his powers.

He led the league in ERA, innings pitched, and strikeouts, with the fourth highest single-season K total of all time (364). He averaged 12.1 strikeouts per nine innings, and had conquered the wildness of his early years to limit himself to 2.1 walks per nine innings. He pitched 12 complete games. He held opposing hitters to a .208 batting average. For lefties, it was even worse: he allowed a grand total of nine hits to left-handed batters all season. Much like Pedro Martinez, Johnson’s stats were even more impressive considering the offensive explosion taking place in baseball at the time.

Only his win-loss record was less than stellar (17-9), but as is often the case with aces, that was more of a reflection on his offense. In one five-start midsummer stretch, Johnson pitched to a 1.18 ERA and wound up losing four games because the Diamondbacks were held to just two runs.

But his magic seemed to run out in the postseason. After winning game five of the 1995 ALDS against the Yankees, he lost five playoff games in a row. However, that too was often due to lack of support. In his brief stint with the Astros in 1998, he pitched two games in the division series against the Padres, gave up three earned runs total, and lost both of them.

Still, if given a choice, few teams would want to oppose Johnson in the playoffs, particularly in a best-of-five series, where you might have to face him twice. As Gary Cohen noted in his pregame remarks on WFAN, “There are no Mets who have had any degree of success against Randy Johnson.” Only Rickey Henderson had much of a history against him at all, good or bad. The rest of the team had either spent most of their careers in the NL while Johnson pitched for Seattle, or were lefty batters who sat down when he pitched (such as Robin Ventura and John Olerud).

The Mets had seen Johnson only once in 1999 and were shellacked 10-1. The Mets’ starter that day: Masato Yoshii, who would start this game as well. After an up and down year, Yoshii was excellent down the stretch, going 5-1 in his last eight starts with a miniscule 1.61 ERA. Still, it would be a tall order to subdue the potent Arizona offense. And it would be just as difficult for his own offense to get to Randy Johnson.

Bobby Valentine did not seem worried, telling Jeff Pearlman of Sports Illustrated, “I don’t think our guys are intimidated by anything.”

Continue reading 1999 Project: NLDS Game 1

It breaks your heart.

It breaks your heart. It is designed to break your heart.

It is designed to break your heart. The game begins in the spring, when everything else begins again,

The game begins in the spring, when everything else begins again, and it blossoms in the summer, filling the afternoons and evenings,

and it blossoms in the summer, filling the afternoons and evenings,

it stops and leaves you to face the fall alone.

it stops and leaves you to face the fall alone. You count on it, rely on it to buffer the passage of time,

You count on it, rely on it to buffer the passage of time, to keep the memory of sunshine and high skies alive,

to keep the memory of sunshine and high skies alive, and then just when the days are all twilight, when you need it most,

and then just when the days are all twilight, when you need it most,