Click here for an intro/manifesto on The 1999 Project.

For the second straight season, MLB would have a one-game playoff to decide the winner of the wild card. In 1998, the Mets could have been a part of that playoff–or made the playoff unnecessary by winning the wild card outright. They were not able to do either, as everyone reminded them all year. But in 1999, they pulled themselves back from the brink of disaster, and now they found themselves in Cincinnati for a winner-take-all contest at Cinergy Field (formerly known as Riverfront Stadium).

The game was originally scheduled for a 2:05 start, but was moved up to 7 in the evening to accommodate the bleary-eyed Reds. They waited out a five hour, 47 minute rain delay in Milwaukee, all the while knowing they had to win to keep their season alive. Much like the Mets, they rallied after a near collapse.

Unlike the Mets, the Reds had few expectations placed on them at the beginning of the year. All they had was a meager $33 million payroll and no real superstars, save maybe team captain Barry Larkin. They shocked baseball by not only being competitive throughout the season, but remaining in playoff picture. They got hot in September, threatening the postseason plans of both the Mets and the Astros, before stumbling against the Brewers in the final weekend.

The Reds’ manager, Jack McKeon, was much older and much more old school than the Mets’ skipper. His team did not celebrate on the field once they finally defeated the Brewers in the last scheduled game of the year. (“What were we going to celebrate?” he asked. “We didn’t win anything.”) But he was fond of trying Bobby V-style gamesmanship. In their head-to-head meetings, McKeon twice pointed out some obscure technicality to the umpires, forcing a Mets pitcher to change his uniform or some piece of equipment (and thoroughly annoying Valentine).

He also had one more glaring similarity with Bobby Valentine. In 11 seasons of managing, which included stints in Kansas City, Oakland, and San Diego, McKeon had never managed in the postseason.

Someone’s unfortunate streak would end here.

October 4, 1999: Mets 5, Reds 0

Temperatures were in the 50s at game time, and would dip into the 40s before the night was over. It rained in Cincinnati through much of the day, and though there was no precipitation at first pitch, there was a mist in the air, and the turf was a bit soaked. “The Mets know if they can win tonight, they’ll be a lot warmer tomorrow,” Gary Cohen noted, alluding to a trip to Arizona that a victory here would ensure. (He also observed that the conditions must have seemed “positively balmy” to the Reds after what they just endured in Milwaukee.)

Hall of Famer and Big Red Machine cog Joe Morgan threw out the first pitch in front of a chilly, pumped Cincinnati crowd. That seemed just a bit odd, considering Morgan would call the game for ESPN. He reported that some of the Mets players “were yelling at me” as he performed his duties. “They have to know I have no effect on the outcome of this game.”

While running through the opening lineups, Morgan wondered if the Reds might have “a slight advantage” on the slick Astroturf of their home park. His broadcasting partner, Jon Miller, reported a conversation with McKeon, who emphasized the importance of scoring first.

The Mets obviously had the same strategy in mind. Rickey Henderson left the last game against the Pirates with hamstring issues, but was well enough to start this game, and lead off with a single to left.

Edgardo Alfonzo followed by smacking Steve Parris’s 1-1 pitch to straightaway center. Its speed and distance took everyone by surprise. Centerfielder Jeff Hammonds

Edgardo Alfonzo followed by smacking Steve Parris’s 1-1 pitch to straightaway center. Its speed and distance took everyone by surprise. Centerfielder Jeff Hammonds

started back leisurely to get it, only to realize it was traveling much farther than he anticipated. Miller’s description was that of a routine fly ball, until it became apparent it was anything but. In the WFAN booth, Bob Murphy was also caught off guard by its flight out of the ballpark. Even the crowd didn’t seem to notice the ball was gone until it dropped just beyond the outfield fence.

Six pitches into the game, the Mets were up, 2-0. The home crowd was stunned, and so too was the home team. Though Parris got out of the inning with no further damage done, the Mets had seized the momentum and would not give it up.

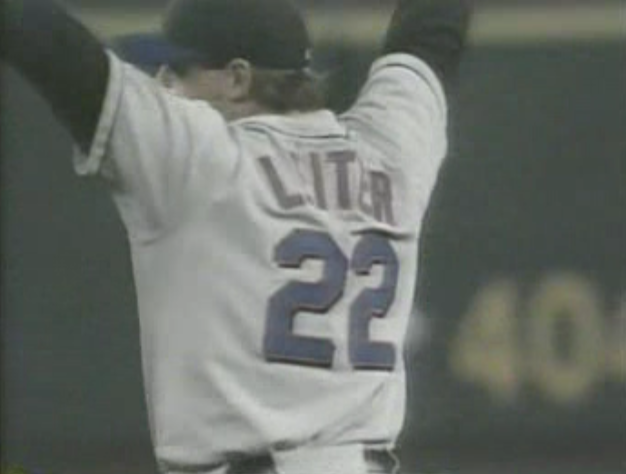

Al Leiter made sure of that. Valentine kept him in reserve for this game, rather than pitch him on short rest in the last game against the Pirates. The wisdom of that decision was demonstrated all night long.

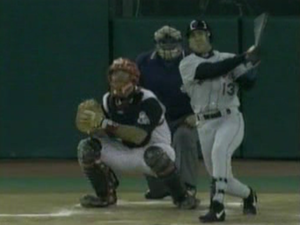

In the bottom of the first, Leiter worked a full count to Pokey Reese, then walked him. When the lefty had trouble, it usually stemmed from walks, and a free pass to start the game might have spelled trouble. “The first inning has been such a worry for Al Leiter,” Murphy noted. But he rebounded by inducing flyouts from Larkin and Sean Casey.

Then came Greg Vaughn, whose hot hitting in September was largely responsible for the Reds’ late surge (he as named NL Player of the Month). Leiter worked a full count, then threw a curveball that froze him, a called strike three to end the inning. From the bench, Orel Hershiser screamed, “You have really great stuff!” Leiter responded with a thumbs up.

In the bottom of the second, Hammonds hit a one-out single to left, but Leiter got

a grounder from Ed Taubensee and a popout from Aaron Boone to end the inning. In the booth, Morgan prophesied that “two runs will probably not beat the Reds”, while Miller insisted the Cincinnati offense was “more diverse” than New York’s and could “manufacture runs with speed”.

But the Reds couldn’t manufacture runs if they couldn’t get runners on base, and

Hammond’s single was the last hit Leiter would allow until the ninth.

In the third, the Mets mounted a two-out rally of sorts when Alfonzo walked and John Olerud hit a double. With first open, the Reds walked Mike Piazza intentionally to face Robin Ventura and brought in lefty Denny Neagle to face him. But Neagle was clearly afraid of a bases-loaded hit, and walked him to force in a run. He induced a comebacker from Darryl Hamilton to end the inning, but now the Mets were in a 3-0 hole.

“The pressure will start to mount for the Reds,” Miller observed, and it certainly looked like they felt the pressure. Leiter pounded the righties in on the hands, and threw breaking pitches to keep lefties off balance. He walked Larkin with two out in the bottom of the third, but then got Casey to swing at a curve in the dirt for strike three.

Leiter proceeded to set down the next 12 Reds in order, pitching 1-2-3 innings in the fourth, fifth, sixth, and seventh. “You can really see Leiter gain confidence as this game goes along,” Cohen observed in the midst of his streak. “If Leiter can pitch through the seventh inning, then hand it over to bullpen, the Mets should be in good shape,” Murphy predicted. As it turned out, the bullpen would not be needed.

In the top of the fifth, Henderson looked completely over his hamstring woes when he swung at the first pitch from Neagle and bashed it high off the left field foul pole for a home run. The Mets loaded the bases with two outs on two walks and an infield single, but Neagle struck out Roger Cedeno to keep them loaded. “The Reds are still breathing!” Miller exclaimed, but they certainly didn’t look like it at the plate.

The Mets tacked on again in the top of the sixth, as Danny Graves, the Reds’ closer, entered the game. Rey Ordonez walked to lead off the inning, and Leiter moved him to second on a sac bunt. (Leiter walked back to the dugout gingerly, prompting some brief warmup action in the bullpen from Kenny Rogers, but he would stay in the game.) After Henderson smashed a line drive right into Casey’s glove at first, Alfonzo laced a double in the gap to score Ordonez, his third RBI of the game.

The Mets were now up 5-0, and with Leiter on the mound, a trip to Arizona appeared in their future. The Reds continued to flail desperately at his offerings, to no effect, and their rare threats were neutralized by Leiter’s guile and bits of good luck. When Taubensee walked to lead off the bottom of the eighth–the first Reds baserunner since the third inning–he was promptly erased on a double play, begun when Aaron Boone’s hit deflected off of Leiter’s glove and right to Alfonzo.

As the the ninth inning began, ESPN showed champagne chilling in the visitors’ clubhouse, the plastic draped across their lockers, and even the wild card winners t-shirt the Mets would drench in bubbly if they could get three more outs.

“If the Mets win,” Morgan noted, “it will be the first time in history someone looked forward the facing Randy Johnson.”

As Leiter took the mound to finish what he started, his performance reminded Morgan of Joe Niekro’s, when he defeated the Dodgers in a one-game playoff to determine the NL West division winner in 1980, though Morgan couldn’t remember if Niekro went the distance. (He did.)

Reese endangered Leiter’s bid for a complete game with a leadoff double. It was only the Reds’ second hit, their first since the second inning, and the first time all night they’d had a runner reach second base. Armando Benitez began to warm up in the Mets bullpen, but he would not be needed.

Leiter fell behind Larkin 3-0, but got him to hit a grounder to Ordonez for the first out, as Reese crossed over to third. He then struck out Casey on a high fastball to bring the Reds down to their final out. In frustration, Casey slammed his bat against the ground, then snapped it in two at the handle. In a more subdued reaction, Valentine pumped his fist quietly in the dugout, one out away from the postseason for the first time in his career.

The celebration was delayed briefly as a fan ran onto the field, giving the Cincinnati crowd one last thing to cheer about (the miscreant termed “some idiot” by Murphy, in an uncharacteristic show of anger by the usually cheerful announcer). Valentine slammed his hat to the ground and screamed “what the fuck!” to no one in particular, worried that this interruption might disrupt his pitcher’s rhythm. Perhaps unneverved, Leiter fell behind Vaughn and walked him. It was the only time all night the Reds had two runners on base at once.

The always emotional Leiter screamed at himself on the mound for losing Vaughn, but he soon made up for it. On an 0-1 pitch, Dmitri Young lined a ball up the middle. It just eluded Leiter’s glove as he came out of his motion. He twirled around to see if anyone could stop it and preserve the shutout.

The always emotional Leiter screamed at himself on the mound for losing Vaughn, but he soon made up for it. On an 0-1 pitch, Dmitri Young lined a ball up the middle. It just eluded Leiter’s glove as he came out of his motion. He twirled around to see if anyone could stop it and preserve the shutout.

Appropriately, it was Alfonzo, the man whose two-run homer served as the keynote address. He ran to his right, slid to his knees, and speared it for the last out of the game. As he came up off the turf, he turned to the outfield and raised a finger to the heavens.

The Mets stormed the field, booed by the Reds fans but cheered on by a few diehards who made the trip to Cincinnati and worked their way down to the seats above the visiting dugout.

Finally able to pop champagne, a soaked, red-eyed Valentine barely knew what to say. “It’s a lot of emotions. I don’t know if I’m smart enough to tell you all of them.”

He wasn’t the only Met who waited a long time for this moment. The win also meant a first trip to the playoffs for John Franco, the former closer who’d been in the bigs since 1984 and spent the entire decade with the Mets, often pitching for awful teams. “It feels great,” he said. “Every time you watch on TV and you watch teams celebrate, you wonder what it feels like. It’s wonderful. This is the first champagne I’ve tasted.”

On Thursday, the Mets were declared dead. By the time Monday was over, the Mets were finally, officially, for-real in the playoffs for the first time since 1988. In a whirwind four days, they had played four games which they had to win or see their season come to an end. They had won all four of them.

Now all the Mets had to do was hop on a plane to Phoenix and try to defeat Randy Johnson.

Now all the Mets had to do was hop on a plane to Phoenix and try to defeat Randy Johnson.