In 1999, I moved into my first post-college apartment, way out in the farthest reaches of Bensonhurst. It was a mere 15-minute walk from Coney Island, a walk I would take many late nights on my way home from the city and somehow avoid murder. Circa 1999, the neighborhood had barely changed since Saturday Night Fever days. When I jogged around the neighborhood, I was an exotic specimen, because people in Bensonhurst did not jog. Old ladies stared at me like I was a wild animal and rotten teens would joke-jog next to me or fake-lunge in my direction, hoping I would flinch.

Tag Archives: brooklyn

Kent Avenue, 2002

She must have been hiding. I’m walking up Manhattan, almost home, when she steps onto the sidewalk out from some darkness, wrapped in a camelhair coat.

She walks alongside me and says, “Can I ask you a favor?” Her teeth almost chatter when she says it. It’s near midnight and cold, but not teeth-chattering cold.

I’ve always been an easy mark for panhandlers. If someone wants my spare change or five minutes of my time, they’re probably going to get it. It has occurred to me I will probably die from being too nice to say no. But this feels different. I sense a want, but no hustle.

I stop, but she says, “No, keep walking, please.” So we continue down the block. A few steps later she looks back to where she’d been, a bar with all its rhubarb and glass clinking. She says, “Some creep was following me from the G train. I ducked into that bar for a minute but I couldn’t tell if he was waiting for me. I just need someone to walk me home.”

Her place is around the corner on Kent, so we walk in that direction. Manhattan Avenue and the bar fade behind us and the night becomes quiet. I make some feint stabs at small talk. Each word that leaves my mouth feels dumber than the last, but I don’t know what else to do. Talk, even dumb talk, feels better than silence. Talk will keep away the creeps, I think.

We reach her building. I wait with my back turned to the front door while she fumbles in a purse for her keys. I scan Kent up and down. I see no one. The bodegas are shuttered and the apartments are dark. It’s so quiet, you can hear the drone of cars rumbling on the FDR across the river, echoing against the night.

I imagine armies of silent creeps hiding in shadows, lurching in the darkness like zombies. They will emerge all at once if I take my eyes off of the street for one moment. Strike one creep down and another will climb over his undead corpse to pursue what he thinks is his. I’ve never seen the world like this until now. It occurs to me that she must see it this way quite often. Every night. Every day.

She unlocks her front door and her mouth says “thanks,” but her face doesn’t. There’s still too much worry and anger there, anger that some creep threatened her. Anger that her best hope for getting home safely was to latch onto a random stranger and pray he wasn’t also a creep. She’s not angry with me, she’s just angry. She should be angry. I should be angry.

I want to give her some kind of apology, but I know it won’t make this night any better and I know it won’t change anything. So I wish her good night and I turn and make my own short walk home and I suppose I am safe but in truth she wasn’t and wherever she is now she still isn’t and so none of us are.

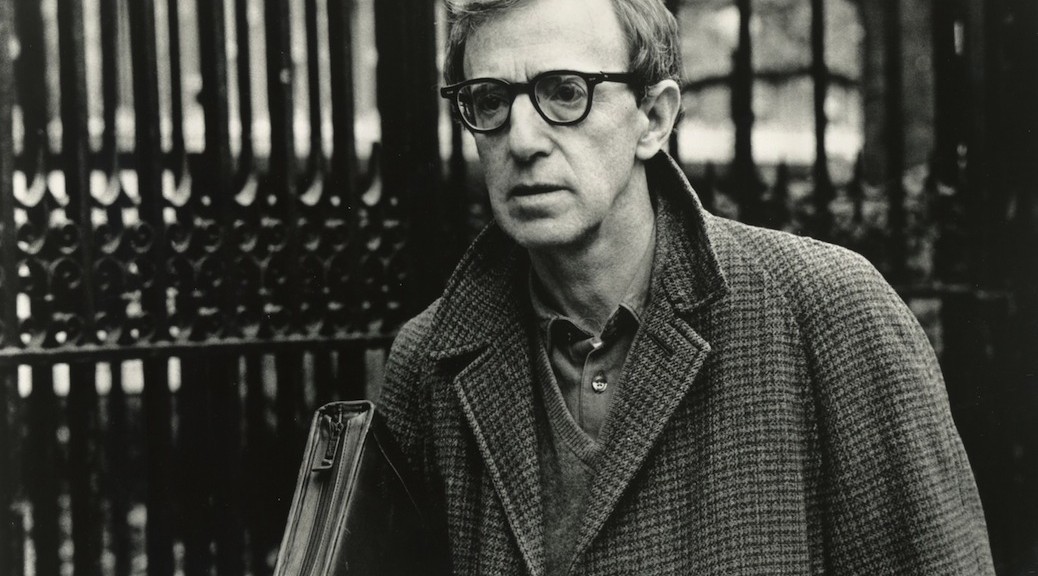

What The Woody Allen Scandal Means For Me, A Very Important Writer

Surely no one wished to be in Woody Allen’s shoes when Dylan Farrow’s new accusations came to light earlier this week. But I assure you, gentle reader, neither did you wish to be me, a Very Important Writer, at that moment. For the news sent me into the kind of turgid self-examination and moral reassessment known only to Very Important Writers, the men to whom the world looks for guidance.

As you are no doubt wondering, how does an allegation of pedophilia make me, a Very Important Writer, feel? As shocking as it may sound to you, this is not a question I could answer immediately.

Foremost on my mind when hearing of Dylan Farrow’s tale of unconscionable sexual abuse and violation of trust was, of course, how would I enjoy Woody Allen’s films again? Could I restrict my enjoyment to one viewing of Annie Hall while sitting on an uncomfortable chair as penance? Would it be more prudent of me to watch his more difficult films such as Interiors instead? It was a quandary not to be considered lightly, and a burden that only I, a Very Important Writer, should be asked to bear.

You can be sure that when I, a Very Important Writer, heard this news, it caused me to pace about my brownstone, lost in the recesses of my Very Important Thoughts. The walls of my humble $3.5 million home soon grew too confining. I phoned up a Very Important Writer friend of mine, but he was busy preparing for the Bread Loaf Conference, and of course also preoccupied pondering the same questions about Woody Allen’s work as I. Could we ever enjoy Allen’s films again, he wondered, and if so what would be a respectable time to wait to do so? We reassured each other that we, two Very Important Writers, should be able to solve these dilemmas in our own due time.

Hoping to clear my head, I took a stroll around my colorful Brooklyn neighborhood, peering in the window of the antique shops and the coffee shops and the charming bistro that used to be a laundromat. I stopped at my favorite watering hole and sipped a 12-year-old scotch while exchanging pleasantries about a local sports team with the ruddy-faced barkeep. I sought solace in a delightful ethnic snack from a food cart while trying out snatches of Catalan I learned during one torrid summer in Barcelona. I believe I made myself understood, for all the deficiencies in my accent, and the considerable drawback that the delightful ethnic snack’s vendor was not from anywhere near Catalonia.

And as I ran across these people, I tried not to burden them with my own burden. To do so would have been unfair, for it is a burden they could not possibly have understood, no matter how much my soul yearned to cry out, You do not understand the grief Dylan Farrow’s lost childhood has caused me, a Very Important Writer.

I returned to my home, which began to seem very much like a prison to me. A prison with an ample garden and vintage pressed tin ceilings, but a prison nonetheless. The latest issue of The New Yorker was waiting in my mailbox, but it gave me no succor, despite a fascinating feature on the oldest bookbinder in Northampton. Nor did I find any relief in a sojourn through an advance reader’s copy of Franzen’s latest, The Tepids of Winona.

Alas, it is only in work that a Very Important Writer can find peace. We are much like the ant in that sense, or the miner, or the humble mechanic who toils on my Audi. And so I resolved to document my inner turmoil, because I wanted you, gentle reader, to know that even I, a Very Important Writer, can not answer every question. I must press forward nonetheless, though I can think of no person who has been hurt more by what Dylan Farrow was subjected to than I, a Very Important Writer.