Click here for an intro/manifesto on The 1999 Project.

As Greg Prince recently pointed out at Faith and Fear in Flushing, October 3 is a significant date in baseball history. There have been quite a few memorable games played that day, from the last games of the 1993 season (sometimes called The Last Great Pennant Race) to game 4 of the 2003 NLDS, to date the only playoff series to end on an out at home plate.

But the biggest, craziest, and most famous October 3 game happened in 1951. As late as August 11 of that year, the Dodgers led the Giants by 13 games. But Brooklyn stumbled, the Giants surged, and the two teams ended the year tied for first place, prompting a three-game playoff to determine the winner of the National League pennant.

After splitting the first two games, the Dodgers led the Giants in the decisive third game, 4-1, as they went to bottom of the ninth at the Polo Grounds. But Brooklyn starter Don Newcombe faltered, giving up back-to-back singles to start the inning, then a one-out RBI double to make the score 4-2. Dodgers manager Chuck Dressen (who’d already made a few curious decisions down the stretch, including ceding home field advantage in the playoff series) went to his bullpen and brought in Ralph Branca to secure the final two outs.

Branca would only get two pitches. Slugger Bobby Thompson took his 0-1 offering and deposited into the left field grandstand for a walkoff three-run homer, forever known thereafter as The Shot Heard ‘Round the World. Radio man Russ Hodges entered the canon of famous sports calls by screaming in disbelief, THE GIANTS WIN THE PENNANT! THE GIANTS WIN THE PENNANT!

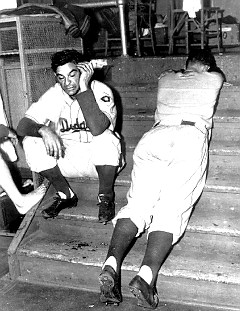

The Giants had just completed a monumental comeback. The Dodgers had just completed a monumental collapse. A heartbreaking photo appeared in the papers next day, showing Branca slumped forward on the clubhouse steps, paralyzed by guilt and grief, knowing he was the architect of yet another Brooklyn choke job.

The Giants had just completed a monumental comeback. The Dodgers had just completed a monumental collapse. A heartbreaking photo appeared in the papers next day, showing Branca slumped forward on the clubhouse steps, paralyzed by guilt and grief, knowing he was the architect of yet another Brooklyn choke job.

Branca would have a decent career, but would never truly live down his role in the Dodgers’ slide, and would not be on the team when Brooklyn finally won a World Series in 1955. Years later, his daughter Mary married a promising prospect for the now-Los Angeles Dodgers: Bobby Valentine.

Much like Branca, Valentine’s playing career hadn’t gone the way he hoped. Nor had his managerial career; he’d captained the Rangers and the Mets for a combined 1,713 games and still not made the postseason. On October 3, 1999, Valentine hoped to lead his own team past a dismal, late-season slide. With a win, they could erase all the doubts and frustrations that had plagued them in September.

On Saturday, as Rick Reed shut down the Pirates, he attended mass and lit a candle for St. Anthony, the patron saint of miracles. On Sunday, Branca arrived at Shea in the sixth inning to cheer on Valentine and the Mets, hoping they could redeem the date in some way.

“October 3 owed one to the family,” he said.

October 3, 1999: Mets 2, Pirates 1

Bob Murphy, original Mets broadcaster and still their radio play-by-play man on this October 3, called it “a beautiful day for baseball!” Temperature at 70 degrees, clear skies, and a near-capacity crowd on hand. He noted a banner held by one of the Shea faithful: “My girlfriend said ‘It’s either me or the Mets’. I said, ‘Let’s go Mets!'”

Murphy’s partner, Gary Cohen, wondered, “Hope he doesn’t change his mind tomorrow.”

A palpable tension hung in the air. You could hear it in the hopeful cheers and anguished gasps of the crowd. You could hear it the voices of Murphy and Cohen. You could even hear it in WFAN’s station IDs. Throughout the broadcast, bumpers promised to bring listeners either the Astros/Dodgers game or the Reds/Brewers game “if necessary”. The implication: If the Mets didn’t win, there was no point in following those other games.

A Mets win relied on the 40-year-old arm of Orel Hershiser, coming off the worst start of his career. Hershiser threw only 24 pitches and recorded only one out, en route to a 9-3 shellacking at the hands of the Braves. He was pitching this game only because it was his spot in the rotation, and the Mets crossed their fingers and hoped for the best.

Hershiser was was opposed by future Met/rookie starter Kris Benson. The Mets had seen both good and bad from Benson. They touched him up for five runs at Three Rivers Stadium back in May but were dominated by him in a complete game effort in July (with an assist from the distracting promotion called Turn Ahead the Clock Night).

Benson had lost six of his last seven decisions, but that was more a function of Pittsburgh’s anemic offense than a true reflection of his abilities. In the first two games of the series, the Pirates batted just .147 and struck out an astonishing 29 times.

And yet, for some reason, Hershiser pitched tentatively to leadoff batter Al Martin, working the count full, then walking him. The next batter, Abraham Nunez, laid down a great bunt towards third, and it took a barehanded grab and throw from Robin Ventura to nab him at first. After a ground out by Brant Brown, Martin tried to steal third. It was a risky move, but made less so when Mike Piazza didn’t even attempt a throw.

The decision would cost the Mets, as Kevin Young followed with a bloop single to left-center, scoring Martin. Warren Morris lined out to second to end the inning, but the Mets were already behind the eight ball, trailing 1-0. The rowdy crowd on hand was suddenly subdued, all too familiar with the Mets’ recent offensive woes. The way they were hitting, every run they trailed by felt like five or six.

The Mets looked to get that run right back in the bottom of the first, when Edgardo Alfonzo reached on an infield single to short, then John Olerud laced a hit into right, hit so hard that Fonzie had to pull up and make sure it didn’t hit him. (“He might have had to go on the DL if he’d been nailed by that one,” Murphy said.)

That brought up Piazza, exactly the man you’d want up in an RBI situation, and he hit the ball hard. Unfortunately, he hit a line drive right at the right fielder. Ventura came up next, and hit a ball that drove Brown all the way to the wall. But he caught it for the final out, and the Mets were turned aside.

As the second inning began, Murphy gave an update on the game in Houston: neither Garry Sheffield nor Kevin Brown would start for the Dodgers. In Brown’s place, September callup Robinson Checo would take the mound. If the Mets won and the Astros lost, New York would automatically get the wild card berth, but chances of that scenario looked slim with an inexperienced pitcher going against Astros ace Mike Hampton. “It’s a shame,” sighed Cohen, “because you’d like to see the Dodgers field their best team.”

Hershiser rebounded to retire the Pirates in order in the top of the second, but the Mets also went down in order in the bottom half. The score remained 1-0 Pirates.

In the third, Hershiser issued another leadoff walk, this one to Benson, who hit .154 on the year. The blunder was soon erased when Martin swung at the first pitch he saw and bounced into a 4-6-3 double play. Pirates first base coach Joe Jones argued the out call at first by replacement umpire Andy Fletcher and was ejected, even though replays showed Martin should have been called safe.

Cohen surmised the Pirates were still hot over not getting the benefit of strike calls in the first two games of the series. He also lamented the loss of so many umps at the end of the season. (“Baseball has definitely suffered for accepting the resignation of 23 umpires,” he opined.) Fair or not, the Mets would take the break, and Hershiser fanned Nunez to end the inning. This marked the 2000th strikeout of his career, but the milestone was only mentioned in passing on the radio, and none of the newspaper accounts I’ve read even mention it. The only number the Mets were interested in was 96: how many wins they’d have if they came up victorious today.

They were also interested in the score in Milwaukee, but that game wasn’t scheduled to begin until 4pm New York time, and the weather forecast was not good: drizzling rain, possibly even snow. “What in the world would they do if that game got rained out?” Cohen wondered.

“I have no idea,” said Murphy. “Play at 9 in the morning, I guess.”

After a quiet third, the Mets once again capitalized on poor Pittsburgh fielding in the fourth. Olerud led off the inning by hitting a ball in hole between first and second. Kevin Young fielded it awkwardly, and had no chance of throwing him out. But he threw the ball anyway, and it skipped into the Mets’ dugout, allowing Olerud to go to second.

Piazza hit a long fly ball to right field, deep enough so that even the slow-footed Olerud could tag up and move to third. (Commenting the weakness of the Pirates’ outfield arms, Cohen observed that Brown’s throw from right “came in on six or seven hops”). Ventura was next, and he smashed a line drive, but right at Young for the second out. The crowd gasped and groaned, thinking they’d seen another scoring chance go by the wayside.

Then, with two outs, Darryl Hamilton came to the rescue, lining a double just between Aramis Ramirez and the third base bag. Olerud trotted in to score, and the game was tied at 1.

The Pirates went down in order in the top of the fifth, and the Mets threatened again with another mistake-aided baserunner. When Rey Ordonez poked a ball into right center, Brown and centerfielder Chad Hermansen couldn’t decide who should catch it. So neither of them did, and as it landed untouched between them, Ordonez raced to second with a gift double. Hershiser tried to lay down a sac bunt but failed, so Ordonez stole third as he struck out, putting a runner at third with one out.

But once again, the Mets demonstrated an uncanny ability to hit balls right into the other team’s gloves. Rickey Henderson hit a bullet to Nunez at short that prevented Ordonez from scoring. “How many times has that happened already?!” a stunned Cohen wondered. After a walk to Alfonzo, Olerud also lined out to short to end the threat.

Meanwhile, in Houston, the Astros were already taking care of business on their end. A bases-loaded walk and a three-run double in the bottom of the first put them up 4-0 over LA. “The Mets can probably forget about any help from the Dodgers today,” Cohen huffed.

In the top of the sixth, after a quick groundout from Benson, Martin hit a double into the gap. The Shea crowd quieted down yet again, save for some more doom-filled groans. Hershiser left the field to an appreciative ovation and gave way to Dennis Cook.

The lefty had struggled lately, and he struggled here, battling Nunez to a full count before finally fanning him. He also worked a full count to pinch hitter Adrian Brown, but could not put the batter away, walking him to put two men on. So Valentine went to his third pitcher of the inning, Pat Mahomes, and he also went full to Young before finally striking him out.

With one out in the bottom of the sixth, Ventura got sneaky and laid a bunt down the third base line. The infielders were playing back and toward first, so even Ventura could beat it out for a base hit. Then Hamilton dunked a bloop single into shallow center to put two men on and mount a threat for the third straight inning. And also for the third straight inning, the Mets could not go ahead. Roger Cedeno flew out to right, and after Ordonez walked to load the bases, pinch hitter Matt Franco fouled out to waste yet another scoring opportunity.

“How many times can the Mets set the table without sitting down to eat?” wondered an exasperated Cohen.

Turk Wendell set down the Pirates in order in the top of the seventh, aided by a great catch by Olerud, reaching into the first base line photo box to record a foul out. During the inning, Murphy broke in with some bad news. “I hate to tell you this,” he said, “but the game in Milwaukee has been delayed by rain.” So even if the Mets could manage to win, they would probably not know their fate for quite a while.

In the bottom half, Rickey Henderson led off with a single, then seemed to come up lame. Cohen wondered if this might be a ploy to make the Pirates think he wouldn’t attempt a steal, but it turned out to be the balky hamstring that plagued him off and on (sometimes conveniently). Melvin Mora pinch ran for him, and stayed anchored to first as Alfonzo, Olerud, and Piazza went down in succession.

Benson had bent but never broke: 120 pitches and seven hits, but he held the Mets to 1 for 11 with men in scoring position. He’d also kept 50,000+ fans tearing their hair out all game long, not to mention the millions watching at home.

“If you’re a Mets fan and you have any fingernails left, you’re not paying attention,” declared Cohen in the eighth inning. “As tension-filled a ballgame as you can possibly imagine. How many of these have we had over the last few weeks, day after day after

day?”

After a quiet eighth inning for both sides, Wendell began his third inning of work and did not look worse for wear. He got Nunez to ground out on another close play at first (“You could’ve called it either way and you wouldn’t have been totally wrong,” said Cohen), and Adrian Brown did the same. But then Young singled, prompting a mound visit from Dave Wallace and more nervous groans from the crowd.

Armando Benitez came to the mound for the biggest appearance of his Mets career so far. It didn’t begin well when Young stole second standing up, which he was able to do because Benitez paid him no mind. With first base now open, Valentine opted to walk Morris intentionally and pitch to the young third baseman, Ramirez. He also made a rare trip to the mound to conference with the hard-throwing righty. Valentine usually sent Wallace to talk to his pitchers; he only went out to the mound in cases such as this, “to make sure Armando has his head screwed on straight,” in Cohen’s words.

“It’s all coming down to this for the New York Mets,” he continued. “Game number 162, inning number nine, and nothing is decided yet.”

Bolstered by Valentine’s pep talk, Benitez struckout Ramirez on a hard slider in the dirt. Piazza applied the tag, and the Mets had a chance to win the game in their final at bat.

Bobby Bonilla led off the inning, pinch hitting for Shane Halter (a September callup who’d briefly played right field in the top of the ninth). The much-maligned Bonilla took a big home run cut, hoping to be the hero, then grounded out softly to first.

Next up, the rookie Mora. Cohen wondered if Valentine would pinch hit for him, but he had few options, as double switches and defensive replacements had depleted most of his bench. In 30 at-bats, Mora had hit just .130 and only had five major league hits to his credit. But he got his sixth here, lacing a single into right field.

That brought up Alfonzo, who’d had countless big hits all year. He had a few more in left in his bat, starting with this one, a single to right that moved to Mora to third, 90 feet away from victory.

Olerud followed, and the Pirates intentionally walked him to load the bases and bring up Piazza. In 1999, it was rare that a manager would prefer to pitch to Piazza. On the other hand, he had grounded into more double plays than any other player in the majors. Plus, the reliever now coming into the game to face him–sidearmer Brad Clontz, briefly a Met the year before–had a history of success against the slugger.

Piazza did not get a chance to make the Pirates regret their decision. Because the first pitch Clontz threw sailed to the right of catcher Joe Oliver. Piazza stepped out of the box and threw up his hands, as if to say, Are you friggin’ kidding me?!

Piazza did not get a chance to make the Pirates regret their decision. Because the first pitch Clontz threw sailed to the right of catcher Joe Oliver. Piazza stepped out of the box and threw up his hands, as if to say, Are you friggin’ kidding me?!

In the on deck circle, Ventura gestured frantically at the plate, but Mora was more than prepared. He’d been a teammate of Clontz’s in the minors, and he was familiar with the way he gripped the ball. Before Clontz fired his first pitch, Mora snuck a peek at his throwing hand, and could tell the pitcher would throw a slider. Mora knew Clontz’s slider well. He knew his slider had a tendency to bounce.

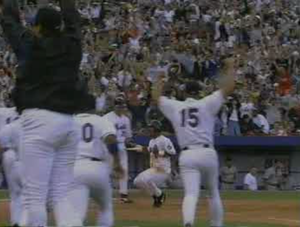

So Mora was probably the best prepared man in the stadium for this insane turn of events. He raced home, then slowed up into an almost Groucho-esque crouch-walk and stopped on the plate. Like he wanted to make sure he wouldn’t miss it, make sure no one could question the fact that he had actually scored a run and won the game.

As the crowd went ballistic and the Mets mobbed Mora at home, the “mojo risin'” refrain from “LA Woman” blasted over the PA. “It may be a long night before we know where the Mets are going,” Cohen shouted over the din, “but we know they’re going somewhere!”

The Mets’ win, as weird and as wild as it was, guaranteed them nothing more than a tie for the wild card. They had clinched nothing. They were assured of nothing but one more game, and a wild card playoff game would technically be part of the regular season. And yet, after everything they and their fans had been through, a celebration was in order.

“It would be more exciting…if you could pop the champagne,” Wendell said after the game. “If the Reds lose, we’ll have to run around and spray things.”

But the weather in Milwaukee would not let them. Rain continued there, with no window in sight. The Mets waited around for as long as they could, hoping the Reds would be able to play and they could watch the results from the safe confines of the clubhouse.

But the weather in Milwaukee would not let them. Rain continued there, with no window in sight. The Mets waited around for as long as they could, hoping the Reds would be able to play and they could watch the results from the safe confines of the clubhouse.

When they could wait no longer, the team made the decision to fly to Cincinnati and get a good night’s sleep. If the Reds won, they’d already be in town for the one-game playoff. If they lost, the Mets would continue on to Phoenix for the division series.

In either case, Al Leiter would start the next game for the Mets. “I’m looking to a worst-case scenario,” Leiter said. “Cincinnati winning and we go to Cincinnati and prepare for the Reds.” He also planned to watch scouting tapes of the Reds as soon as he could.

It was a wise plan. After a rain delay of almost six hours, the Reds finally defeated the Brewers, 7-1. At nearly empty County Stadium, disgruntled ex-Met Pete Harnisch earned the win. They would host the Mets for a one-game playoff to determine the wild card winner.

As for Ralph Branca, no matter what happened next, he felt a bit redeemed by the Mets’ efforts on this date. “This takes away 80 percent,” he said. “But it still owes us.”