These days, there’s no shortage of people casting dire warnings about Donald Trump. Each time the president makes another statement, millions of people point out the eerie similarities between his latest “tactic” and those employed by brutal dictators of old.

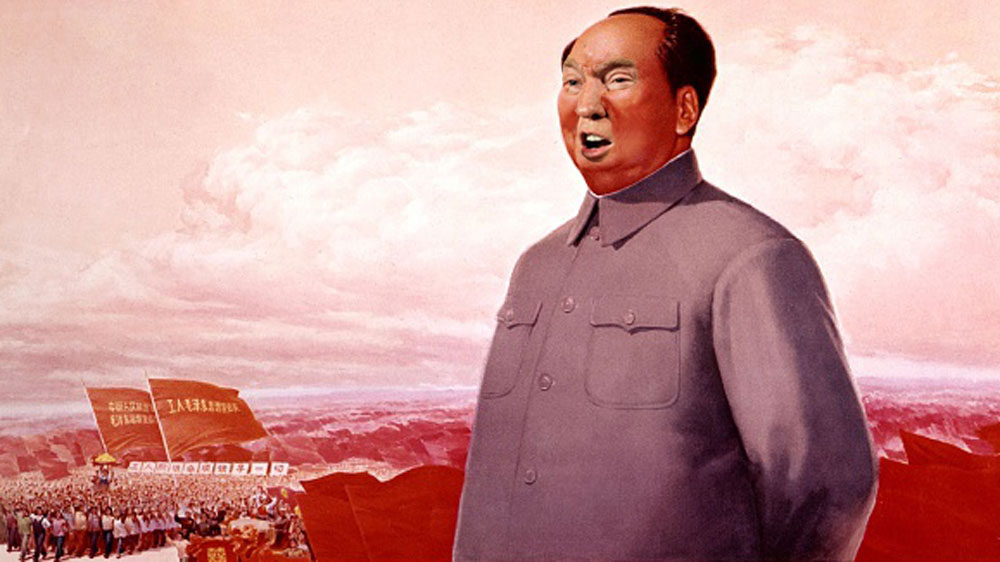

The dictator to whom Trump is most often compared is Hitler, an extreme comparison that would be totally unfair if not for the fact that many of his closest advisers are full-blown white nationalists. At the risk of splitting hairs while the world burns, Trump’s style of governing (such as it is) does not remind me so much of Der Fuhrer, whose horror was at least meticulously planned. His first chaotic days in office remind me more of a completely different despot: Mao Zedong. Specifically, they call to mind Mao’s Cultural Revolution.

I’ve long been fascinated by hermetically-sealed cults of personality, like North Korea, and regimes that attempted to halt history in its tracks, like Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge. But the place and period that fascinates me the most is China under the Cultural Revolution (which ran roughly from 1966 until Mao’s death 10 years later), which combined a cult of personality with an insane push to erase history into one horrifying amalgam.

During the Cultural Revolution, everyone in China—all 1 billion of them—was taught to worship Chairman Mao as if he were a god. Mao had always been officially revered, but this period elevated him to an insane, untouchable level. Mao made sure he remained at this level by fomenting a climate of “permanent revolution” in which any vestige of the past was questioned, then destroyed. The result was a roiling chaos that left everyone too confused, terrified, and exhausted to question anything Mao had done.

Even if you know nothing about Mao or the Cultural Revolution, this has an obvious, superficial resemblance to Trump. His election was an attempt to destroy all political norms that preceded it—both the Clintonite neoliberal consensus and the staid fiscal/intellectual conservative wing of the GOP. In the place of both of these, Trump has created a new political reality that revolves exclusively around his own whims.

But how are the two men specifically similar? Allow me to demonstrate.

A disdain for intellectualism and ‘elitists’

Though he once aspired to be a schoolteacher, throughout his life Mao harbored a deep animosity toward intellectuals and elitists that stemmed from his peasant roots. He was an autodidact who felt he had taught himself better than any teacher could have. For him, a lack of formal learning was to be worn as a badge of pride. This message resonated deeply with the nation’s peasants, who held their own resentments against wealthier, more well educated city folk.

In the early years of the Cultural Revolution, Mao encouraged students to question and rebel against their professors, implying that everything the people really needed to know could be learned through his teachings and example. All other forms of learning were bourgeois affectations, of no use in a revolutionary society.

At every opportunity, Mao stirred up resentment against teachers and ‘class enemies,’ such as families that had owned shops or rented out land before the communists took over. From Frank Dikötter’s The Cultural Revolution, a comprehensive history of the period:

This might sound like someone you know. Trump received more formal schooling than Mao and hails from a far richer background, but he holds a similar belief that the workings of his own brain are superior to all fancy book learnin’. And though he is himself a billionaire (probably), he constantly rails against ‘elites’—most often, the media and those who preach the poorly-defined precepts of political correctness. Like Mao, Trump knows these sentiments speak to a large chunk of the country that feels the same way.

From a piece in the Washington Post, comparing Trump to his more intellectual predecessor:

Q: What books are you reading?

A: Look over there. There are some books. pic.twitter.com/9cItkOPMQ7— Peter Hamby (@PeterHamby) January 18, 2017

From The Atlantic, one Trump supporter’s rationale:

Ever-shifting targets

When the Cultural Revolution began in earnest, bands of Red Guards—teenagers, mostly—roamed the streets, looking to expose and punish “counterrevolutionaries” in positively medieval ways. The earliest and worst violence began in the schools Mao criticized, as students accused teachers they hated of harboring counterrevolutionary thoughts. The accused were then paraded before crowds, beaten, humiliated, tortured, and often killed. Some people, once they realized they would be the next target of the Red Guards, chose suicide instead.

From the schools, the violence quickly spread throughout the country, as Mao hinted darkly about “rightists” hiding in plain sight in the ranks of the Communist Party itself, and proclaimed, “To rebel is justified!” This constant search for enemies, and the resulting violence, plunged the country into a constant conflict that was civil war in all but name.

But if rebelling was justified, against whom were the Red Guards supposed to rebel? It was difficult to say, because the political winds shifted so often that no one could keep up with them. Groups would form to attack a target—a local party leader or factory boss, usually—under the belief that they had the Chairman’s backing. Then, these groups would find out Mao backed their target instead, and without warning they were labeled the counterrevolutionaries. Within the Communist Party itself, longtime leaders would be revolutionary heroes one day, and sent to a work camp for “reeducation” the next. Future premier Deng Xiaoping was in and out of Mao’s good graces multiple times, as were many of his contemporaries. The scrambling to be on Mao’s “correct” side was unceasing.

Initially, the Red Guards made sure their ranks were composed solely of people who were “born red” (children of revolutionaries who fought with Mao) and had no members who were “black” (from “capitalist” class backgrounds). Then, literally overnight, the definitions of these terms changed. Longtime Party members were suspect, making their “red-born” children suspect as well, while those from “black” backgrounds were suddenly preferred because they had not been exposed to this corrupting influence. From Dikötter:

Often, the real motivation behind these shifting political winds was pure revenge. Mao nursed grudges religiously, and relished in exacting vengeance at exactly the right time. During the Cultural Revolution, Chinese citizens followed his example. People were often denounced as “enemies” by neighbors who wanted to exact revenge for one slight or another. For almost a decade, the country tore itself apart with one act of revenge after another, as citizens followed the chairman’s example.

Likewise, Trump rails against his enemies in the harshest possible terms, but exactly who those enemies might be changes often. Even before he won the election, Trump signaled his presidential policies would be charitably described as fluid. From CNBC:

In no area is Trump’s slipperiness more evident than his attitude toward financial elites. Last year, Trump railed against rivals like Ted Cruz and Hillary Clinton for being “controlled” by Wall Street, and The Big Banks. Though this was a clear play to his elite-hating base, the act was so convincing that Wall Street declared itself “terrified.” Also from CNBC:

Once in office, Trump had different targets in mind. It was no longer Wall Street who needed to be attacked, but the troublesome regulations that kept banks from lending to his wealthy buddies. from Vox:

On the personal level, Trump’s demand for unquestioning loyalty means that someone who’s in his good graces one day can be cast outside the next due to the merest mistimed gesture. Everyone from Joe Scarborough to a formerly anonymous college student can be set upon by his minions if they displease him. They can also be welcomed back into his camp if they show the proper deference.

Trump previously said Adelson was using his billions to turn the other GOP candidates into “puppets.” Feels like a long time ago. https://t.co/aqhXEF2qro

— Benjy Sarlin (@BenjySarlin) February 9, 2017

In the worlds of both men, only the most sycophantic of toadies are spared this constant yo-yoing of favor. For Mao, it was longtime nominal premier Zhou Enlai. For Trump, it’s Sean Hannity.

The buck stops nowhere

When Mao’s call for a Cultural Revolution predictably sowed violence and chaos, he was nowhere to be found. He successfully separated himself from all the consequences of his words. The cult of personality around him ensured that he would never be blamed for any mistakes made in his name. Such errors could only result from not following his words and example closely enough. From Dikötter:

Likewise, Trump’s poorly conceived executive orders—especially the travel ban—have led to a similarly predictable (if less violent) amount of confusion and disorder. And yet, he has not conceded (and likely never will) that any blame for the failings of these orders—executed on his signature alone—should fall on him. Much like Mao, those who believe in him do so with such fervor that he can place all blame for these disasters on a failure to follow his orders correctly. Like when he was “not allowed” to phase in the disastrous travel ban (from CNN):

The cult of Trump is so unquestioning that, despite his projected image of an alpha male attack-dog businessman, he can blame his shortfalls on a lack of stamina without fear this image will be tarnished. For example, see his bitchy, diplomacy-shredding criticism of the Australian prime minister, which was termed the result of fatigue brought on by almost one full hour of phone calls (again from CNN):

‘Self reliance’

A belief in “self reliance” might seem to run counter to the aims of a communist society, where all economy is supposed to be produced collectively. But Mao preached this concept often during his reign, and especially during the Cultural Revolution. Communities were told to pull themselves up by their bootstraps and work to make more arable land, more passable roads, more viable factories, and to work day and night to do so—with as little help from the state as could be managed.

The rural village of Dazhai was pointed to as the exemplar of this can-do Horatio Alger-esque spirit. In Dazhai, Mao crowed, all citizens pulled together, made do with as little as possible, and quite literally moved mountains through sheer force of will. All the country was instructed to do the same.

In truth, Dazhai was a Potemkin village, its accomplishments constructed for propaganda purposes. The reason Mao preached such self reliance is because China’s split with the Soviet Union (a split that had its roots in Mao’s hatred of Nikita Khrushchev, who exposed the atrocities of Mao’s idol, Stalin) robbed the country of vital Russian aid. This, and other disastrous projects done at Mao’s behest (like The Great Leap Forward), had left the Chinese economy in shambles. The foregoing of state aid was declared a virtue because in truth, there was no state aid to give. From Dikötter:

While he comes at it from a decidedly different viewpoint, Trump also makes appeals for bootstrap-ism that resonate across a wide swath of the electorate, from the mythical Small Business Owners to the anarcho-libertarian strain. With entitlement reform at the top of the congressional GOP agenda, and the new president likely to rubberstamp whatever they put on his desk, the hidden message at the heart of Trump’s words are largely the same as Mao’s: help yourself, because no one’s coming to help you anymore.

Family ties

Other than Mao, the foremost figure of the Cultural Revolution was his wife, Jiang Qing. A former actress long relegated to the sidelines, Mao made her the chief attack dog of the Cultural Revolution. Whereas Mao preferred vague statements, Jiang Qing named names, in the most brutal manner possible. It was understood that to oppose her was to oppose Mao, and that when she named a target, she did so with the chairman’s full knowledge and consent. From Dikötter:

Apart from gifting her the spotlight she craved, Jiang Qing’s role at the head of the Cultural Revolution also enriched her financially. When Red Guards gathered up artifacts of “the old bourgeois world” from “class enemies,” she was given her first pick of the loot:

This dynastic confining of executive power in one family is common in dictatorships. It is not common in our nation, yet Trump was permitted to appoint his daughter and son-in-law to official White House positions. This is why we now find ourselves in a position where a retailer’s decision to drop Ivanka Trump wear can be considered a political act, and why another White House advisor can retaliate by touting those clothes on a cable news show. It’s also why, though all of these actions violate longstanding laws about nepotism and emoluments, not a thing will be done about any of them.

Constant fear of war

Other than providing a smokescreen to keep himself in power, Mao’s main motivation for the Cultural Revolution was to declare China (and himself) as a bastion of “true” communism. Mao felt the Soviet Union had turned its back on revolutionaries across the globe and wanted them to look to him instead. This engendered a bitter split between China and Russia, one that occasionally threatened to explode into actual hostilities.

When the initial fervor of the Cultural Revolution began to fade, one way Mao stoked its flames again was to raise threats of an imminent Soviet invasion. Citizens were told to prepare for a long, bloody battle and commanded to build tunnels and trenches that could accommodate entire cities underground for the duration of such a conflict. Such work called for skilled engineers, but in the anti-intellectual environment of the Cultural Revolution, all the engineers had been jailed or hounded into hiding. People dug anyway, with disastrous results. From Dikötter:

As for Trump and fears of war, well, where to begin?

From The Guardian:

In summary, Trump’s chaotic style of governing make his administration a dead ringer for the chaos of the Cultural Revolution, in tone if nothing else. Obviously, Trump has not yet done anything to cause widespread famine, death, and destruction. For now.